Cycling has become quite polarising recently: there has certainly been a backlash towards the bicycle revival. It has become yet another battlefield in the ongoing culture wars which we seem to be living through.

For some people, a false binary emerging. Cycling, who until fairly recently was seen as a poor person's transport, is now middle class, urban, possibly pro European and left wing.

This makes me a little bit sad, because for me bicycles spark so much joy; and because I have cycled in places like Tanzania and Tokyo who I connected with people precisely because I was out on a bike. Cycling can be an excellent way to meet new people who may be different from you, and it remains the one of the most logical ways of getting about in a town or city.

I would quite like it if you bought my book about bicycles, which goes into more detail.

It was well-reviewed: 'rich, honest, engaging and entertaining...' said one reviewer. 'Fascinating, hilarious and thoughtful,' said another. "

'I was almost brought to tears,' said Life In The Saddle in a review which also said that '...it should be read much more widely.' Sadly, it was not read widely, in fact not enough people bought it for me to break even. So the unsold copies stare at me when I'm working in the loft.

It's a mix of memoir and adventures on sensible bicycles. A central thesis is that when we start using bicycles for transport we became healthier and happier.

It's definitely not an anti-car rant, I don't think. Although I did see some places (usually poorer countries) where car ownership in was increasing that were becoming increasingly polluted and less safe for children to live, precisely at the time when some enlightened urban planners in rich countries were realising the benefits of bicycle friendly cities where you can breathe, rather than see, the air.

Having said that, 2020 was possibly not the year to launch a book which advocated in favour of cycling through China.

Anyway, here's a long and Christmassy extract, anyway. A version of which originally appeared in Boneshaker Magazine

You can also get the Bicycle Clip Diaries on your Kindle.

If you cam here looking for Get the Eason Look, it has sold out of its initial print run. But you can get an on-demand copy here:

https://www.blurb.co.uk/b/7923021-get-the-easton-look

Enjoy, and I hope you get a new bike for Christmas x

If the person on my street WhatsApp group who recently complained about bike parking 'when there isn't enough space for cars' is reading this, I'll happily give you a copy for free.

===

I was fearless on a bike back then...

Even travel has got competitive, and people thrive on tips from the so-called experts. You must see this, eat here, and do this thing. I don’t have many tips for travellers, because so many of the best things happen when things don’t go according to plan, or when the plan is vague in the first place. But one thing I do recommend is to get your hair cut in as many countries as you can: unlike eating or sleeping, the whole process has not been made inauthentic by the travel industry.

So I get my hair cut in a shoe shop that doubles up as a hairdressers. The middle-aged woman who shortens my hair chats away rapidly and enthusiastically in Spanish, sometimes bringing in her friend to the conversation. I understand approximately 30 per cent of what they say, but I can tell it’s all very friendly and enthusiastic. I use non-verbal clues to work out the bits when I’m supposed to show assent, approval, and occasionally horror at what is being said.

I’m in Manizales to go mountain biking in the National Park Les Nevados, Villamaria. It’s a pleasant university town in the mountains, which at just over 2, 000 metres, isn’t all that high by world, or even Colombian standards. Although it would easily be the highest European city if it moved a few thousand miles west.

What it lacks in height, it makes up for in ‘abrupt topography’; this means that some of its streets are steep. So ridiculously steep that they are perfect for ‘urban mountain biking events’, where people ride fast down almost vertical streets and jump down concrete steps. Until fairly recently such riding would have been reckless, if not impossible, and the idea of cycling down mountains would have been seen as a cry for help. Now it’s an industry.

We are driven in a pick-up truck to 4,138 metres above sea level. My new holiday friends are a pleasant and sporty couple from Chattanooga. I think they are as excited as I am to be here, high in the Páramo wilderness, between the treeline and the snowline. Our destination is the Parque Nacional Natural Los Nevado, ‘the snowcapped national park’.

It’s just the three of us, and our Colombian guide Miguel who, it turns out, was a national mountain bike champion the previous year. He rides enduro, stage mountain bike races, where your downhill speeds are more important than your overall climbing ability. In the back of the pickup are our hardtail GW and Santa Cruz mountain bikes: black, low slung and menacing and with a touch of the BMX about them.

I think back wistfully to my days as an extreme sports pioneer. I was approximately eight, and unstoppable on my Raleigh Strika. It was a bicycle which hardly anyone remembers and rarely with fondness. It was a scaled down version of the Raleigh Grifter, itself a heavy and unsuitable British copy of a BMX. The Strika, which my Nan’s neighbour had won in the bingo, had the most uncomfortable saddle in the history of all bicycles. It was wide and made of black foam, which caused abrasions when you were wearing shorts, which, in 1981, I nearly always was. But I loved that bike, non-functioning suspension forks and all.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Raleigh still made nearly all bicycles that were ridden by British children. But you see their designs getting more and more faddish as the firm struggles to keep up with foreign competition and a whole new way of doing things. The Raleigh Commando, for example, was a military-themed bicycle which was available in camouflage, although it was really a shopping bike with a fancy saddle.

Special mention goes to the Raleigh Vektar, a BMX with a large plastic housing on the top tube. It contained what was optimistically described as an ‘onboard computer console’, with a speedometer, FM radio, and a ‘sound generator’.

Kids’ bikes today are technically much better to ride: lighter, stronger, faster. But I suspect that none will be discussed with the same shared sense of nostalgia in twenty years’ time. Looking back, the big difference between the British bikes we didn’t want, and the American bikes that we did was air.

The ability to jump up on your bicycle and, for a moment, be in the air was quite a remarkable thing in the history of how we ride. Who knows which bicyclist first experienced this phenomenon? An accident, presumably. You’d imagine it wasn’t a pleasant experience. On a big heavy steel bike not designed for it, there seems to be a pull to ground. An old bike would, perhaps in a northern accent, decline the opportunity to hurl itself off a ramp. ‘I prefer it here on t’ground, if it’s all the same to you and that’s where I’ll stay.’

Even though the Strika wasn’t designed for jumping, you could manage it, if the angle of the jump was just right. With trial and error, you could stay on, making adjustments for the heavy front end. You could even jump over stuff: down steps, over a fire, each other, sometimes. The best run was to leap down the steps past the caretaker’s office at Chandlers’ Ridge School. Then down the bank and out through the gap in the back of the fence, and back in a hi octane circuit.

On the right bike, jumping is an amazing feeling. To leave the Earth, for just a nanosecond, on a bicycle and to land it cleanly feels right. To add a slight flick or a twist is even better. It’s unaccountably fun. Why is this so? It’s a mystery.

I was fearless on a bike back then, without a fully developed frontal cortex and having been raised on Evel Knievel. I was in a biker gang, too. Admittedly there were only two of us, me and Ben Scaife. We scoured our suburb for things you could jump down, across or over; in between going to Cubs and listening to our anthem, Van Halen’s ‘Jump’. I shudder at the thought now. But in those days, it was all about getting as much air as possible, and Evel Knievel was an important role model.

Like us, he was a thrill-seeking adventurer, living for kicks. By the 1970s he was also a doll – I mean action figure – on a toy motorbike which in reality failed to do any of the spectacular stunts from the TV commercials. Although the actual Knievel didn’t always succeed in his jumps, and people knew this.

His bike choice seems totally inappropriate and early shows featured – incredibly – a 750 cc Norton and a 750 cc Triumph – big heavy English motorbikes, which were eventually replaced by a big, heavy American Harley XR-750.

The showmanship is part of the real Evel’s appeal. An early jump features a box of rattlesnakes and a pair of mountain lions, exactly the kind of thing we would have jumped over if they had been available in North East England at that time.

Watching the videos, with our modern health and safety sensibilities, is engrossing. But you want to intervene: as he falls, he flips like a rag doll, his body flicking this way and that, whacking into hay bales at speed. He is then hit by his riderless bike in a final act of cartoonish indignity.

In those days, the good ol’ boys on Evel’s team stood him up just as soon it was possible to do so, something which draws cheers from the crowd. He flops forward propelled by well-wishers who grab and shake his head roughly. Well done, Evel, you fell off your bike again. Just a few breaks and possibly irreversible brain damage.

Whereas today you’d avoid such impact where possible; if it happened, you’d stabilise the patient’s head as much as you could until medical professionals arrive on the scene.

His efforts look particularly strange in comparison with today’s motocross trick rider videos. They do back flips and no-handed jumps, or change direction in the air, in a stunt sequences which look they have been planned meticulously. With Knievel, it was more binary: a straight jump – you either make it or you don’t.

It’s possible see him as encompassing the tragic side to the American Dream. He wants to stop, but can’t. The roar of the crowd keeps him going, as do contractual obligations and various injections. He looks fucked. His injuries were famous and multitudinous, and his 433 reported bone fractures earned him a place in the Guinness Book of Records. He had an ‘internal morphine pain pump’ surgically implanted in order to ease the pain, apparently.

In real life, he was not a superhero, more of a bully and a crook. In 1977 he assaulted a promoter over the contents of a book, Evel Knievel on Tour, which alleged that Evel used drugs and abused his family. The daredevil exacted his revenge in a violent baseball bat assault. At the time, inevitably, both of Evel’s arms were in slings, so he needed his partners to attack the unarmed promoter.

We didn’t know that then, and nor would we have cared. This guy did mad jumps, and probably inspired more bicycle-related mishaps than any other figure in history. By 1982, when Raleigh got into the world of BMX, Evel’s brand of hairy-chested red meat virility and white jump suited theatricality was out of touch and irrelevant by the early 80s. The squares in the toy industry cancelled his contracts. But the notion that you could jump on a bicycle was firmly lodged in our young minds.

The bicycle industry needed the BMX craze, because people weren’t buying bikes for transport any more. And kids needed a BMX, because they were cool. 10 Speed racers were for older kids and prefects.

In the run-up to Christmas 1983, I was coming to the end of a fairly long-term strategy to achieve my ends, a BMX Burner, or maybe a Tuff Burner with sweet mag wheels. I’d been on the Strika for so long that my inner thigh skin rash was a more or less permanent feature. But I’d given up in defeat after it had been made clear to me that there would be no new bike.

Even as a kid I understood that times were tough in the early Eighties. Obviously we were spoilt in comparison with the kids in Tanzania, who have to fetch water and herd goats and don’t go to school. But factories were closing down and the steel industry – amongst many others – was in decline. The 1980s might have been a time of champagne, red braces and amusingly massive cellular phones down south, but up north we used bread clips for Spokey Dokeys.

My Dad no longer worked on the steel or ICI, and his job working for the local authority was safe, but interest rates had doubled. Years later I found out that my parents had struggled to hold on to their house. The industrial heartlands were decimated as people got on their bikes to areas where there were jobs. Cousins and uncles headed south, and people went to work on oil rigs.

The places that made the things that made us proud were now becoming embarrassing, rust belts, towns that people made jokes about. The empty buildings would later come in useful for raves and then yuppie apartments, if you live in one of those towns which have yuppie apartments. As opposed to one of those towns which just has charity shops and social problems because decades later there are still no jobs.

There were streets where hardly anybody had a job in my town, and pit villages close by suddenly found themselves purposeless.

But something strange happened on Christmas Day in 1983. A pedal poking out through wrapping paper in the dim light. A bit of gold handlebar.

A Raleigh Super Burner, and proof that dreams can come true. I promise that I’ll oil its chain and promise not to jump over rattlesnakes. I’ll be good and do my homework and never get another detention or top the demerit chart in my form class again. In the moment I saw that pedal peeking out from its crude wrapping, this was all true. No subsequent present has come close. Perhaps that Raleigh Super Burner is the high that I’ve been chasing ever since.

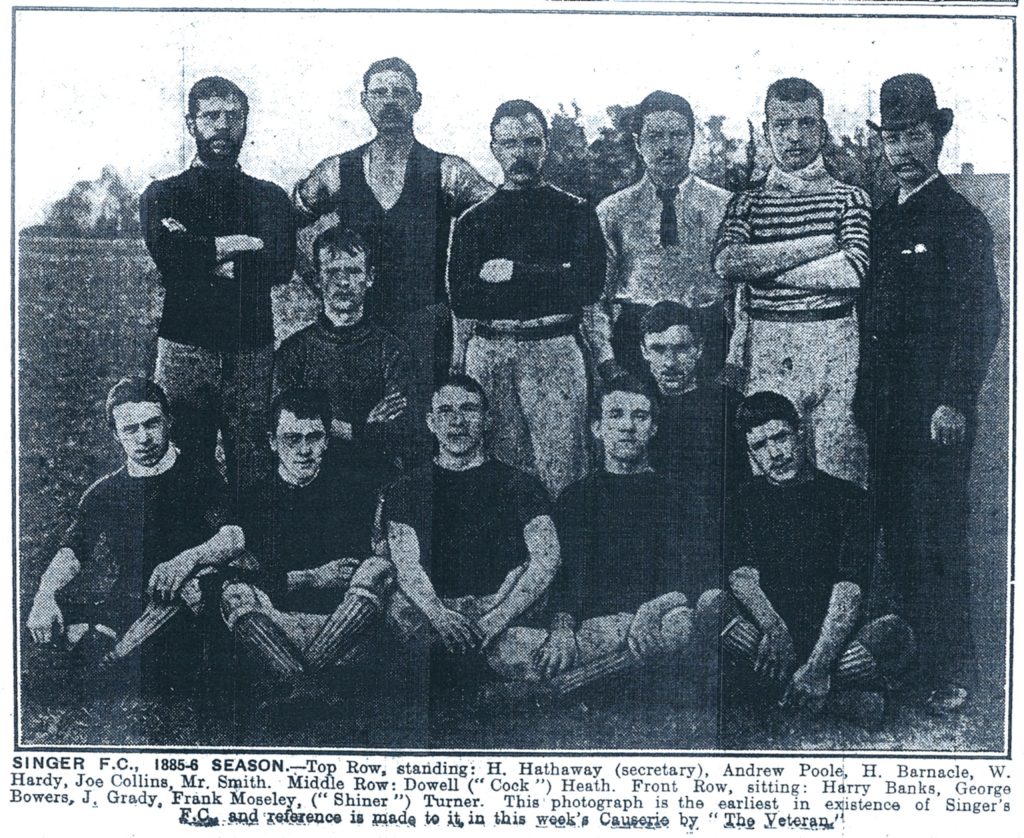

I’ve always had a soft spot for Coventry, the football team.

Perhaps it’s the mad kits they had in the 80s. The unnecessary stripes, and they were the only team to turn up in a brown away, so far as I remember. I loved the flair. In 1889 their kit was pink and blue, according to Wikipedia, so they have a long history of sartorial flair.

(fact: the T stripes were for Talbot, whose cars were made in the city. They toyed with calling the team 'Coventry Talbot'. They don't make collars on sports shirts any more...for health and safety reasons, possibly)

Like Middlesbrough, it’s a town which has been let down over the decades by successive governments who quite frankly did not give the impression of caring much about industrial decline, so long as shareholders were happy. In my head Coventry are a bit like us, a bit of a yo-yo club, but that turns out to be false memory as evidence suggests they enjoyed 34 consecutive years of top flight football between 1967 and 2001.

Anyway, I wish them luck but obviously I would much prefer if Middlesbrough beat them in the Championship Semis and we get back in the Premier League again.

As for Coventry the town, these are my reflections on the town, as seen from the saddle of my bicycle. An extract from my book, the Bicycle Clip Diaries, which is still available to buy on this very website.

"I’m brought back down to earth by Coventry, where I am forced to stop for minor pannier repairs. I am excited that there is a statue of James Starley, the father of the modern bicycle industry and Coventry is arguably its birthplace. I feel quite emotional. This is our industrial heartland.

Starley was one of the reasons there used to be more than 400 bicycle manufacturers in Coventry before the war. He was a manager at the Coventry Machinists’ Company which started out making sewing machines, but went on to make the first mass-produced bicycles ever. And if you believe their 1885 advertisement, they supplied tricycles to the Sultan of Morocco, and the King of Siam. Coventry-made bicycles were exported all over the world. Rudge-Whitworth, Triumph, and BSA all had bicycle factories here, as did Coventry Eagle, Coventry Hawk and Coventry Majestic. For a while just adding Coventry to your name implied a mark of quality, like Champagne for sparkling wine.

The people in the bike shop are underwhelmed by this information. One of them tells me about the statue of Frank Whittle, the designer of the first jet engine to be used to actually power an aircraft. He took out a patent for a turbojet in 1930, although the RAF described his invention as ‘impracticable’, and he had two nervous breakdowns.

Cycling through Coventry, I can’t help wondering if it would look different if Britain had invested more heavily in turbojet technology as a form of defence in the 1930s, instead of sailing submarines* along canals for the benefit of children? I think, too, of AlanTuring, another wartime maverick. Harangued over his sexuality to the point where he killed himself, dying lonely and in shame, having been forced to keep his war work top secret.

With the benefit of hindsight, and a few tweaks here and there, Britain could be different. Perhaps if they had listened to experts a bit, been a bit more open with their tech in peacetime, and not persecuted people so much we could lead the world in bicycles, computers and rocket science. And present day Coventry wouldn’t have an atmosphere of downbeat confusion, as if it is trying to work out its purpose.

As it stands, it is impossible to cycle through the city which inspired the song ‘Ghost Town’ without it entering your head as your earworm. Arriving at the roofless cathedral is a moving experience. To people of my generation and older it is synonymous with concentrated aerial bombing. Indeed, ‘to Coventrate’ briefly became a verb in both English and German, to devastate an area through bombing. In a single raid in 1940, two thirds of the city was damaged, including factories, much of the medieval city centre and a couple of hospitals. Hundreds died.

Here, I learn that just after the attack, the provost who had tried to save the cathedral from Luftwaffe bombs inscribed ‘Father Forgive’ on one of the remaining walls.

The majority of people at the cathedral now are groups of children, for whom the bombing of Coventry and its factories must seem an abstract concept. A sign on the steps says ‘No skateboarding or similar activities’, which suggests there has been a youthful indifference to the site’s history which has been noticed by the relevant authorities. I think of Philip Larkin and, so far as I can tell, the only literary reference to cycle clips:

Hatless, I take off

My cycle-clips in awkward reverence.

These are lines which would no doubt confuse a young person today. You would have to pre-teach so many alien concepts: being hatless, church etiquette, cycle-clips.

I feel conflicted: my own awkward reverence for the site, the suffering, a place where so many lives were lost for reasons worth remembering. But something about the tone of the sign has got my back up. I want to change it.

‘Look kids, this whole mess all started out with people telling each other what to do, intolerance, the demonization of outsider groups, all that kind of jazz so fine, skateboard, ignore signs, have fun, do whatever you want. Just do it with love in your heart and without upsetting others, and don’t ever think of bombing someone, for any reason, ever’ or words to that effect.

Instead of a red line through a skateboard, I want the symbol to be the kid in the Kes poster doing the V sign in defiance of authority. But like most people in real life I’m far too law-abiding to carry out nearly all of the acts of minor sabotage suggested by a rich interior world.

So instead I continue to ride, daydream a bit, get lost, and spend more time than most people do in one of Coventry’s inner-city suburbs, the name of which I never learn. Large numbers of people seem to be inactive in the middle of the working day. Are we less industrious? Or is there less work, because the bicycle factories are all in Taiwan these days? Not that I’m judging, as technically I’m idling too.

I finally manage to get out of Coventry, needing to make time after all that dawdling. I’ve still got eighty miles to go, with a couple of heavy panniers and nobody to share the wind."

*the submarine reference is to an earlier part of the book:

"Squint and you could be in Cornwall as you pass Frampton-on-Severn, with its hedgerows and gentle, unfolding greenery. Soon you reach Gloucestershire and Sharpness Canal, a shortcut from the River Severn to Gloucester. It is pretty now, and impossibly quiet, but was used by bulk oil carriers until the mid-1980s; and in 1937, two British submarines, apparently heading for a fête where children were charged a penny to go onboard, passed this way too."

Image source: http://www.ccfpa.co.uk/?p=59628

Hello,

This month (April 2022), I will donate £10 for every copy of my book (the Bicycle Clip Diaries) I sell to the Ukraine Disasters Emergency Committee.

That's the full cost of the book, you'll still have to pay the postage.

To do this, please click here here

Many thanks,

Nick

photo © Nick Raistrick. Drawing © my postman whose dad enjoyed the book.

It has been a month when clients decided to pay late; my mortgage lender is somewhat less flexible about matters of a financial nature. Such is the gig economy.

Obviously, things are much worse in Ukraine, and I was going to donate some money to the Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC) fund. But I also needed a new bicycle bag. I couldn’t really afford both.

So this bar bag was my solution. The entire cost of the bag goes to DEC. And whilst I’m sure there are people who would yell ‘get off the road you snowflake virtue signaller’ at the sight of it, I don’t mind that too much. Virtue signalling is less bad than, say, not signalling at a roundabout. Which does happen, you know.

And possibly virtue signalling encourages people not to be so proudly mean, or uncaring about a cause. I'm old enough to remember people saying that the campaign to end apartheid was trendy, and it possibly was. But still a good thing. Is it virtue signalling to wear a poppy?

Of course, the best thing to do about conflict around the world is to ride a bicycle instead of being dependent on a petrol vehicle...or even an electric one, in the UK, where so much of our electricity comes from gas-fired stations. I digress.

In an ideal world, there would be no product review of anything less than 10 years old, because of finite resources being depleted rapidly for short term minority benefit. So I’m reluctant to say too much about its performance.

But so far it’s turning out to be an excellent bag. I can see no reason why it will not last for decades, when hopefully it will look like an anachronistic reminder of a short and long-forgotten conflict that was resolved quickly.

Well done to Wizard Works for making the bag - in the UK too- and although they seem to have sold out of Ukraine stuff, there are other ways to donate.

Please don’t send them baby clothes or pebbles with messages of peace. You should do your own due diligence on that. But DEC is a goods start and it seems, from colleagues in the humanitarian sector, that cash is better than sending stuff to a war zone.

This month*, I will donate £10 for every copy of my book (the Bicycle Clip Diaries) I sell to DEC too. That's the full cost of the book, you'll still have to pay the postage. Order directly from me, here

*April that is. Not March as there's only one day of March left.

I was in the bike shop the other day… not inside it, obviously, due to the lockdown, but close enough to wistfully look at the tyres on hooks and think about all the bike shops I’ve known.

Big up the bike shops, a beacon of light in these dark times, especially Rayment Cycles in Brighton. And here's another extract from the Bicycle Clip Diaries which is obviously still not available in all good book stores, but from my website, details below.

"I love bike shops. They are happy places, full of optimism and promise. Even when I don’t technically need anything, if I’m in a new town, or a new country, I’ll go in and have a poke about. When I worked in an office near the City, I loitered in bike shops during my lunch hour to the extent that I thought I might get barred, expecting my grainy image to appear on a photocopied ‘do not serve’ list of the type you get in small town pubs. In the same way that Woody Allen loves his jazz clubs as much for the people as the music, I love the atmosphere of a bike shop as much as for the items on sale.

Like everything else, bike shops have changed over time. They used to be small places called something solid like Cartwright & Sons, where you’d open a creaking door and a comforting bell would sound. The door would close with a satisfying and solid ‘kerthunk’. After a suitable pause an elderly gentleman would pop up from behind a counter piled high with dusty inner tube boxes, perhaps banging his head on a row of orange-walled, sensible tyres hanging from a ceiling.

He would ask you what you want, and if you mumbled ‘Just looking, thanks’ he would probably come at you with a broom. Nobody tried. Retail was not thought of as a leisure activity. The exchange of cash for goods was essentially utilitarian.

The idea that bike shops would one day become spacious, well-lit places with pop music, staffed by young people with name badges? It was inconceivable not so long ago.

The Lycradollar hadn’t taken over: even serious cyclists still wore woollen jerseys which would stay wet for several weeks after a ride, with things like West Bromwich Corinthians Cycling Club written on them. Such emporia would sell bicycles from a suspiciously incomplete range of manufacturers, which would have a non-removable Cartwright & Sons sticker somewhere on the frame. You could still easily pick up a pair of bicycle clips, no questions asked.

It made buying decisions easier, obviously, because you wouldn’t spend hours looking at the reviews of possible purchase options, because there weren’t any. You trusted in your bike shop guy, and maybe the catalogue. So long as you didn’t want Skyway Mag wheels, yellow mushroom grips or any of the new Japanese or American BMX accessories that had started to flood the streets in the early 80s, you were fine.

Bicycle shops in Britain today are often upbeat places where you are encouraged to spend time. Spaces which unashamedly appeal to the emotions, and there is nothing like the emotion of someone considering their next bicycle.

I love the drama in the earnest exchanges. The hypnotic sales talk is confusing and yet pleasing, a combination of poetry, engineering and aspiration. The retailer-shaman uses terms like ‘lateral stiffness’ and ‘responsiveness’ to overweight men with such seriousness that they seem not to question what these words might actually mean, or what difference they will make to their overall life chances.

You can tell that bringing your actual working bike into such a space is not quite welcome; like a wheelchair user in a trendy nightclub, they can’t throw you out, but you know they don’t really want you there. There’s something about a bike which has actual dirt, scratches and mudguards amongst all the pristine new bicycles they want you to buy that shatters the showroom illusion they work so hard to preserve.

Bike shops in rich countries have videos on loop which show young athletes going fast in the blue-skied Alps. It’s never a red-faced, middle-aged man in an angry exchange with a taxi driver on the Holloway Road in November drizzle. They don’t want real bikes, with a stolen front wheel or a flat tyre. They are selling the dream of the new you that you can become. If you spend just that little bit extra on the Dura-Ace or the Nimbus 2000 crankset.

It’s a bashful dance, the shop assistant in suppressed awe of the elixir of customer’s wealth. The customer is equally aware of the shop assistant’s sharp-edged calves. It’s no accident that they make you wear shorts if you work in a bike shop.

The young, skinny salespeople clearly spend a lot of time on bikes they themselves presumably couldn’t afford without a staff discount, and several years of extra shifts.

The customers have read the reviews, and they want access to advanced innovative engineering, which has been designed for elite level athletes. To feel that they deserve to be in this club. So they spend thousands of pounds on bicycles to achieve a weight loss which could have been more easily achieved through eating one less pie.

‘Some of our less refined customers, Sir, well they are happy with the mid-range bike, but I can see you are a real cyclist, the kind who would appreciate stepping up to full carbon. I can tell you’ll respond to its responsiveness, its lateral stiffness. But without upgrading to electronic gear shifting, it would really be a false economy.’

I like them all, but when you’ve found your Goldilocks, just right, bike shop, it’s wonderful thing. The place you can trust for repairs, and which is run by enthusiasts who tolerate your questions. Maybe a place where there is cake and coffee and they let you into the workshop and show you how to true wheels, like Roll For The Soul in Bristol. So I had high expectations of my first African bike shop..."

Spoiler alert: African bike shops are a disappointment; to find out why, read on.

https://nickraistrick.com/ - £12.99, including postage

or on Kindle

In Brighton, you can also pick up a copy from Tilt (café in Fiveways).

(if you are unwaged, DM and I'll try and send you a copy as a gesture of goodwill. Ditto key workers and bike shop staff)